In addition to our weekly newsletters, we drop a monthly “Deep Dive” on highly relevant topics in the business of sports & entertainment that should be on your radar.

In this edition, we’re analyzing how international investors are positioning themselves to enter the American sports ecosystem. It’s a 10 minute read and probably one of the most comprehensive pieces of information you can digest to get smart on this subject.

Unlike nearly every other market in the world, U.S. leagues have historically been run by domestic ownership – for instance, the NFL has been 100% American-owned throughout its history.

But that’s changing. New ownership structures, various geopolitical strategies, and evolution in private capital rules are making international capital a far greater force in American sports than most realize.

Let’s get into it.

MONTHLY DEEP DIVE

How Global Investors Are Entering American Sports

Historically, team ownership was hyper-local – family-run businesses and local aristocrats owned teams as a community development project or a source of hometown pride. Louis Edwards, who ran a successful, Manchester-based meat processing company before acquiring Manchester United in 1965, epitomized that era of community-rooted team ownership.

But that model has inverted. Look at the English Premier League (EPL). In 2002, every team was locally owned – today, 75% of the teams are financed by outside capital. Cross-border investing has now become the defining trend of modern sports, permeating everything from club acquisitions to stadium financing.

The same dynamic extends beyond club ownership to sports infrastructure and league expansion. In just the past few months:

The NFL is broadening its international series with new games slated for Australia and Mexico City – adding to London, Dublin, Germany, and Brazil

Fanatics, Fox Sports, and OBB Media will debut the “Fanatics Flag Football Classic” in Riyadh next March, featuring Tom Brady and current NFL stars

As American leagues pursue global markets – cultivating economic partnerships with international investment funds, family offices, and sovereign entities, foreign investors are reciprocating, turning their attention towards domestic sports assets that were once considered off-limits.

Exhibit A: Qatar Investment Authority acquired a 5% stake of Monumental Sports & Entertainment – the holding company for the Washington Wizards, Capitals, and other domestic sports/media assets – for $200M.

Historically, international ownership of U.S. franchises has been rare.

Think:

Hiroshi Yamauchi’s tenure with the Seattle Mariners from 1992 to 2013

Mikhail Prokhorov’s ownership of the Brooklyn Nets from 2010 to 2019

However, these isolated examples were billionaires, not institutional financing. It’s long assumed that American leagues would never open their gates to international capital to capture controlling stakes, preserving the “sanctity” of American Dynamism.

That assumption is now murkier than ever. Global expansion is accelerating viewership by tapping into new audiences and capital pools – unlocking new revenue streams through international games and media rights. The same forces making U.S. sports global brands will inevitably make them global assets.

So, will international institutional ownership of American sports franchises become a reality?

We think that time is coming a lot sooner than most believe.

What we’ve found is that the perfect storm of private equity exposure, league-level rule changes, and sports-adjacent real estate investments has opened new gateways for global capital to enter.

But to paint this picture, let’s rewind to the league that pioneered the playbook for international ownership.

English Premier League (EPL) Set The Precedent

In 1992, as an escape hatch for top clubs – Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal, and Tottenham – who were frustrated by the equal revenue-sharing model of the old English Football League, the newly formed EPL instituted a modern governance model that gave clubs control over their own broadcast and sponsorship rights, turning teams into independent commercial entities.

That same year, the league signed a 5-year, £304M television deal with Sky Sports (BSkyB), a transformative agreement that injected much-need financial support into English football. As The Guardian wrote in 1992:

“The chief gainers from the new deal will be BSkyB and associated commercial interests, the Premier League clubs – each guaranteed an annual minimum of £1.5M to help make the crummier parts of their grounds fit for human habitation…”

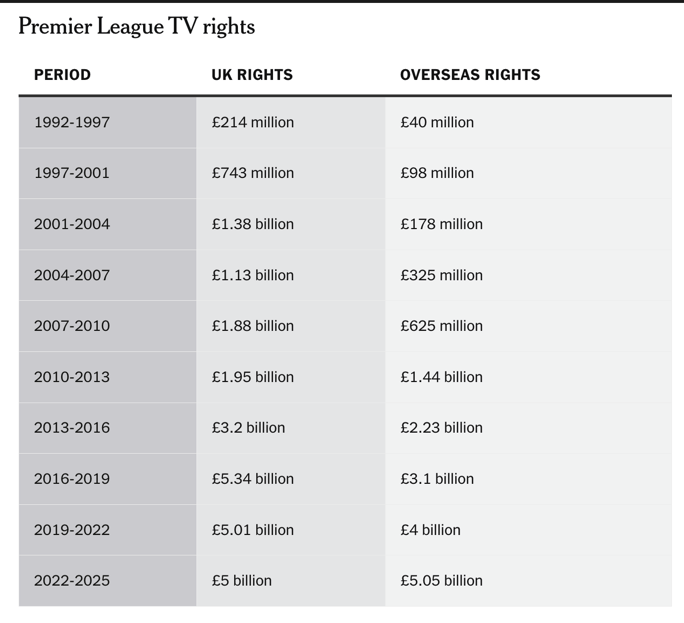

By the 2000s, the EPL became a global product – its overseas media rights doubling in value with nearly every renewal as international audiences tuned in to watch global stars like Thierry Henry and Cristiano Ronaldo.

Photo Creds: EPL’s overseas TV rights 2x’d in value in nearly every renewal from 1992 to 2013.

Three key forces converged to make the EPL a perfect ground for international investors:

Globalization & Media Value: The surge in overseas broadcast revenue signaled to international investors that EPL was no longer a domestic product in the UK, but emerging into global entertainment IP.

There was a premier opportunity to invest early in this growth curve as clubs could soon become global brands

International investors leveraged their home-market expertise to accelerate club footprint abroad — like Fenway Sports Group amplifying Liverpool’s brand across the U.S. or Abu Dhabi turning Manchester City into a Middle Eastern cultural export

Exit Liquidity for Legacy Owners: Many English families had owned their clubs for decades, often buying controlling stakes for under £1M. As valuations soared, the arrival of international capital offered a generational exit.

Valuation Arbitrage: Compared to U.S. sports franchises, Premier League clubs were dramatically undervalued. Many were loss-making operations through the early 2000s yet sat atop international brand potential. For investors with a long-term horizon, it was the perfect buy-and-build scenario.

Investors tightened spending and ran clubs like real businesses

Modern stadiums, facilities, and digital tools turned clubs into revenue engines

International tours, sponsors, and media deals expanded fanbases worldwide

And in 2003, the EPL officially internationalized ownership. Roman Abramovich acquiring Chelsea for £140M was a watershed moment, injecting Russian oligarch capital that eventually turned around the club: Chelsea achieved multiple EPL and Champions League titles in his tenure.

That opened the door for a new class of investors:

2005: The Glazer family’s leveraged buyout of Manchester United introduced American ownership to football.

2008: The Abu Dhabi United Group acquired Manchester City, turning a mid-table team into a global powerhouse and cementing Gulf capital’s influence in global sports.

2010: Fenway Sports Group bought Liverpool, incorporating U.S. sports-style operations into European football clubs.

By the 2010s, American investors dominated the cap table with the likes of Arsenal, Crystal Palace, Fulham, and Burnley.

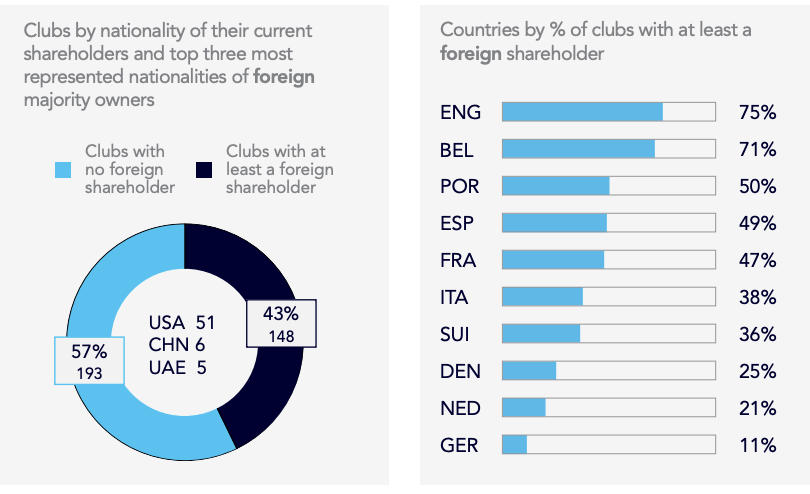

Other European football leagues followed suit. As the 2023 CIES report highlights, even traditionally domestic leagues like La Liga and Ligue 1 had nearly half their clubs backed by international capital.

Photo Creds: European football clubs have significant exposure to foreign capital.

Is the EPL a Mirror for American Leagues?

Not exactly.

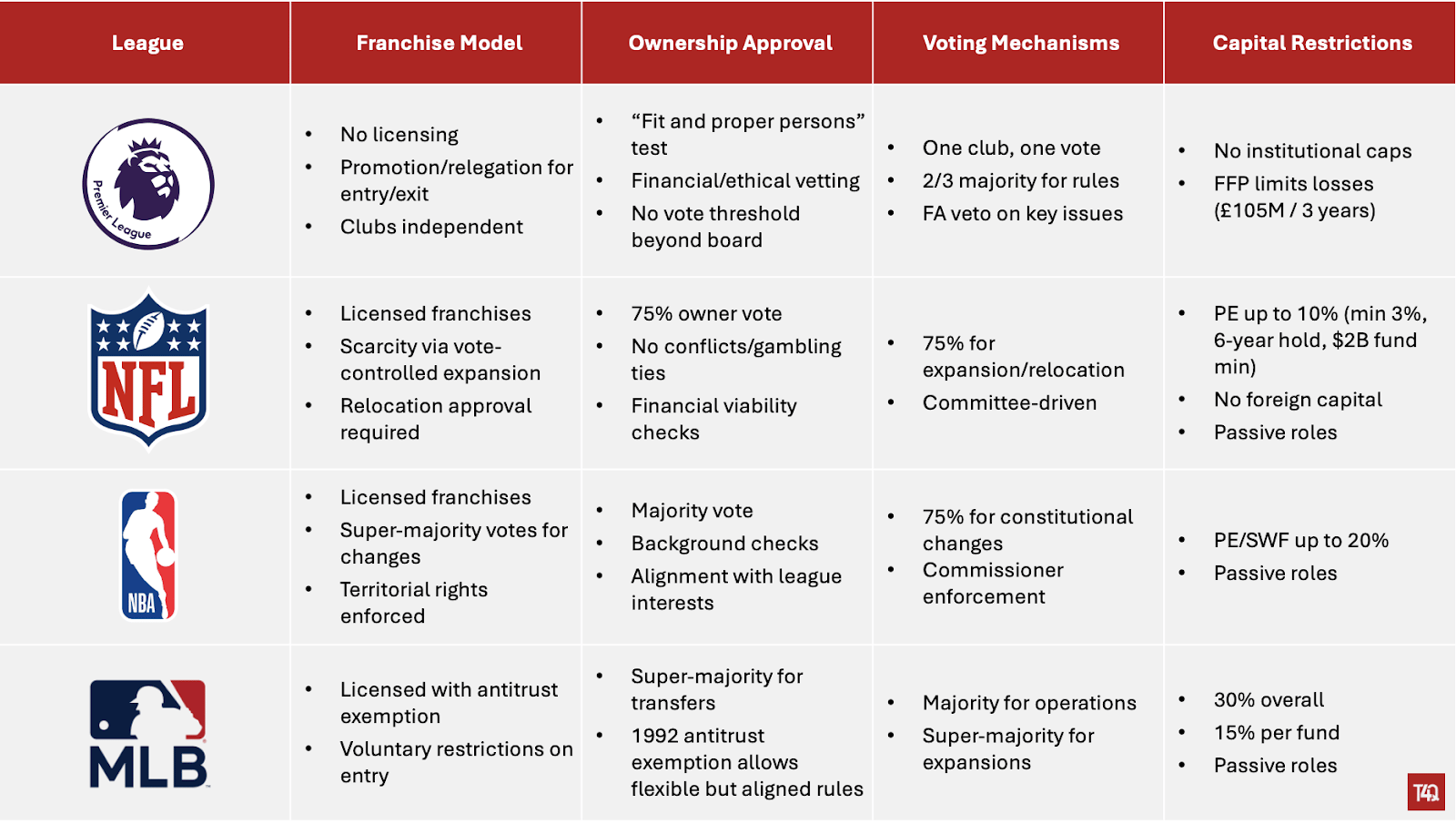

U.S. leagues are approaching a similar inflection point – expanding abroad, selling media rights globally, and forging deeper ties with international investors to fund the next era of growth. Yet, unlike European football, American leagues operate within a distinct regulatory and cultural framework that has long safeguarded domestic ownership.

EPL vs. American League Ownership Frameworks

The chart above highlights the key contrasts between the EPL and major U.S. leagues. American leagues operate as tightly controlled ecosystems, protected by antitrust exemptions that allow them to coordinate governance in ways most European leagues can’t. That level of control - from ownership approvals to rigorous financial vetting - has created the kind of structural stability that’s made U.S. franchises some of the most desirable assets in the world. But that same enforcement also raises the bar for who gets in.

In fact, the latter is one of the strongest deterrents for potential owners – even American billionaires – who are disinterested in dealing with the hassle of disclosing substantial amounts of financial information and litigation history. Existing owners also have a say, and in an industry where familiarity matters, the “known quantity” bidder usually wins.

On top of that, capital restrictions block international family offices and sovereign wealth funds from acquiring controlling stakes in franchises.

So, where’s the “in”?

American leagues have begun relaxing restrictions on institutional capital, allowing owners to monetize partial stakes while reinvesting proceeds back into their teams. Now, nearly two-thirds of NBA teams are backed by private equity money.

Even the NFL, historically the most restrictive, opened the door to PE funds in 2024. During Leaders Week London 2025 last month, Commissioner Roger Goodell described the change as a success:

“It’s really there to try to give our teams an opportunity for liquidity, but it’s brought in a different perspective of the business of sport and the potential for growth.”

International investors now gain indirect exposure to American sports through their limited-partner commitments in sports-focused PE funds like Arctos, Dynasty Equity, and Avenue Capital, as well as through the broader sports vehicles launched by major asset managers such as Ares, Apollo, and Sixth Street. These funds have become the primary entry point for global capital seeking exposure in U.S. sports assets.

And these relationships can get very creative.

Take TWG Global, Mark Walter’s holding company that invests in sports, entertainment, and technology, for example. Its portfolio includes the LA Dodgers, LA Sparks, Chelsea FC, and Cadillac’s Formula One Team. While TWG isn’t a traditional PE fund, its structure allows it to raise outside capital – a key detail in the evolving sports-investment landscape.

In April 2025, TWG announced that Mubadala Capital, Abu Dhabi’s investment arm, would anchor a $10B syndicated investment as part of TWG’s $15B equity raise. TWG simultaneously committed $2.5B into Mubadala and acquired a minority stake in the asset manager.

By providing fire power, Mubadala gained deep exposure to TWG’s growing U.S. sports portfolio:

“By combining our institutional expertise and capital resources through this unique alignment of interests, we are strengthening our joint abilities to access and scale high-quality investment opportunities globally.” – Hani Barhoush, CEO of Mubadala Capital.

Two months later, the Buss family agreed to sell a controlling stake of the Los Angeles Lakers to Mark Walters / TWG – an example of a high-quality investment opportunity generated by Mubadala Capital and TWG’s partnership.

Photo Creds: Total returns from American sports team have beaten the S&P 500 in the last decade.

Where Will the Next Cycle of Owners Exit to?

Private equity firms have wasted no time snapping up minority stakes in sports franchises. Private equity is now buying in at $5-10B valuation ranges:

Sixth Street bought a 3% stake in the New England Patriots at a $9B+ valuation and a 12.5% stake in the Celtics at a $6B valuation.

Ares Management acquired a 10% stake in the Miami Dolphins at an $8.5B valuation.

Arctos Partners took a 10% stake in the Buffalo Bills at an estimated $5.3-5.8B valuation and 8% in the Los Angeles Chargers at ~$5.1B.

Unlike traditional buyouts, these investments aren’t necessarily driven by financial engineering or change in operational control. Firms are instead bullish on the long-term compounding value of scarcity, media rights growth, and global brand equity.

A typical PE fund operates on a 5-7 year investment horizon-year timeline, targeting a 15-20% IRR in that period – essentially aiming to double its investment in 5 years. LPs expect liquidity by the end of that cycle, which creates an interesting dynamic: achieving that liquidity increasingly depends on finding investors with deeper pockets.

Let’s apply this math to the Patriots.

Suppose Sixth Street were to exit its position from the Patriots by 2030. They’d need to sell into a ~$20B franchise valuation just to meet baseline targets. That assumes no leverage or debt paydown since the NFL is highly restrictive on borrowing.

Meanwhile, the league’s ownership rules are evolving. If the NFL eventually raises the institutional cap from 10% to 20%, a single investor buying that full 20% stake in the Patriots would need to deploy $4B+ in equity - roughly the scale of an entire sports-focused PE fund.

In practice, several funds would likely pool capital together to fill the allocation. But the thought experiment underscores how liquidity at these levels will require a broader set of buyers. As valuations climb, domestic private equity funds will continue to anchor the market, but the scale of capital needed to sustain liquidity will likely require sovereign wealth funds and international family offices to be involved alongside them.

What Happens When Controlling Owners Want Out?

This question is more relevant than ever. Many controlling owners will soon be passing the baton to the next generation. The average NFL owner is 72, with seven over 80, and eight teams still held by founding families. In the next decade, second-generation heirs will inherit billion-dollar franchises tied up in illiquid wealth and a potential 40% federal estate tax waiting for them when ownership officially transfers.

Some second-gen owners may decide to sell because they’re not interested in running the team. For others, it may be a matter of liquidity.

Imagine, hypothetically, the Kraft family decides to sell the Patriots in 2040. If the franchise doubles every five years – the PE target return – it would be worth ~$80B by then. Under current NFL rules, a controlling owner must hold at least 30% of equity, meaning an incoming buyer would need to put up $24B to buy the team.

There might be only five individuals on Earth who are capable of, let alone consider that investment.

For the Krafts (or any future seller) to get their price, the league would have to either:

Relax restrictions and allow PE funds to take controlling stakes, or

Open the door to international institutional capital

Either way, if valuations keep compounding, the harder it will become for the leagues to keep the gates closed on global institutions.

How Else Can International Investors Get Strategically Involved?

Beyond private equity or direct team stakes, global investors have always found ways to tap into the American sports asset class:

Sponsorships: Sovereign wealth funds are increasingly using sponsorships for global brand reach. Emirates became the title sponsor for NBA’s In-Season Tournament (now the Emirates Cup) in 2024.

Intellectual Property: Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) has invested tens of billions in LIV Golf and its acquisition of EA Sports. LIV drew superstars like Bryson DeChambeau and Jon Rahm from the PGA and almost merged with the PGA. Through EA Sports, PIF will own gaming IP of major leagues like the NFL and MLS – we previously talked about how they have the pulse on sports fandom in our newsletter here.

Media Platform Investments: International capital has long favored media adjacent ecosystems. Mubadala remains a major co-investor in Endeavor with Silver Lake; PIF previously invested $500M in Live Nation before divesting in 2024.

But we think there will be two new unique strategic developments between American league ecosystems and international investors.

The first big opportunity lies in the new IP American leagues are creating. NBA Europe and NBA Africa are both selling franchise rights, with global players like CVC Capital and Qatar Sports Investments already in talks for the European assets. These entities understand the global markets better than anyone, making them ideal operators to expand the NBA's global footprint. It also allows the NBA to build bridges between themselves and these new ownership groups.

The second opportunity is sports-related real estate. There are now 48 existing and 32 planned venue-anchored developments across the five major American sports leagues – from Atlanta’s $5B+ Centennial Yards Project to D.C.’s $6B+ RFK Stadium District and Chicago Bears’ next stadium project. Institutional investors like Arctos are positioning accordingly, recently appointing Thad Sheely (former Hawks COO and Head of Real Estate at State Farm Arena) as operating partner to strengthen value creation at the intersection of sports and property development.

Not every owner wants to be a developer. Mark Cuban admitted selling his controlling stake in the Mavericks to the Adelson family (majority owner of Las Vegas Sands) because sports ownership is evolving into real-estate ownership, which wasn’t his game.

This is where we’ll likely see more international strategic involvement, specifically from GCC nations. Qatar spent $200B+ developing the stadium and mixed-use infrastructure for the 2022 World Cup, Saudi Arabia has pledged $10B+ to its Qiddiya City sports-and-gaming megaplex, and the UAE built Dubai Sports City, a 50-million-square-foot sports district. Their track record in hospitality and urban megaprojects makes them natural strategic partners for the next generation of U.S. stadium districts.

Final Thoughts

The future of international ownership in American sports remains uncertain, but history offers a clear precedent. The globalization of sports leagues made international ownership a clear possibility. While tales from the EPL story may not perfectly mirror the league-controlled structures of U.S. sports, the same forces are now in motion: institutional capital involvement and private equity liquidity all point toward a future where global entities hold controlling stakes.

One way or another, international investors will remain deeply woven into the fabric of American sports – whether through adjacent properties, new league IP, or the growing frontier of mixed-used real estate.

As with every asset class, international capital follows opportunity. And right now, that opportunity is American sports.